Waiheke

Island

An

Outline of the Early History

up to the Arrival of the Europeans

©

2011

Waiheke Island Historical Society, Inc.

Onetangi, Waiheke Island

©

2011

Waiheke Island Historical Society, Inc.

Onetangi, Waiheke Island

An island as strategically well placed as Waiheke as well as rich in natural resources did not take long to attract the settlements of the first inhabitants of New Zealand.

The ancient Maori name for Waiheke was Te Motu-arai-roa, ‘the long sheltering island’. It sheltered canoe traffic passing through the Tamaki Straight from bad weather coming in from the north. The island’s inhabitants were able to watch the strait from the watch towers of their pa. Travelers plying the strait must have wondered what wealth lay hidden in the island’s bush clad valleys and within its deep estuaries opening out to the south.

Waiheke Maori must have felt exposed to attack. Over the centuries there were periods when pa building absorbed all the energies and resources of island communities. Most of the forty-six pa, marked with a red dot on the map in the Maori display in the Historical Museum, were built on headlands and high hills as safe refuges in times of war. Some were probably built to secure stocks of winter food from marauders: like kumara, taro, dried fish, kiore, and birds preserved in fat. Earthworks are all that now remain as evidence of the prodigious labours of the pa builders. The heavy timber palisades with their fibre lashings have long since rotted away leaving nothing but telltale stains in the light coloured Waiheke soils.

Seen from far out to sea and from distant shores the island stretched low across the horizon. The crowns of huge kauri, rimu and totara reached above the skyline. At the beginning of Polynesian contact the dense bush covered the whole island, with kauri the dominant species. Pockets of pohutukawa, puriri and taraire occupied their own ecological niches in the valleys and along the coast. Many other trees and shrubs important to Maori found their own niches wherever there was moisture, shelter and light.

Fire once destroyed the podocarp forest at the western end of Waiheke. Dense groves of kanuka and manuka quickly replaced the burnt out kauri, rimu and totara. The fires were probably started accidentally by Maori clearing bush for garden plots during long dry spells.

The island was rich in natural resources important to the Stone Age people who first settled here. The Maori term for those times was Te-Ao-Kohatu, the world of stone. The open sea, the sandy beaches, the rocky shores and the tidal estuaries swarmed with kai moana: fish, shellfish and crustaceans, crayfish and crabs. Seals hauled out on the beaches. Freshwater streams of pure clear water trickled down every little valley, providing habitat for native trout, eels, fresh water crayfish and fresh water mussels. Eels lurked in the swamps and wetlands.

Maori used the raupo which thrived in swamps for thatching and the roots and pollen heads for food. Outcrops of greywacke and basalt boulders provided raw materials for stone tool makers. The local stone was not of the first quality. High quality basalt was imported from Great Barrier Island and tough hard argillite from the South Island.

The forest supplied timber for building huge war canoes and waka small enough for fishing. Timber was used for house frames, for garden tools and for utensils and implements of every kind.

The forests produced vegetable foods, greens, berries and piths, as well as birds for the ovens and cooking pots.

Ngati Paoa claimed the island as tangata whenua from about 1700. Its people were observed to be strong, vigorous and wealthy, with energies to spare beyond mere subsistence. Their canoes, houses, implements and hunting and fishing equipment were often decorated with carvings. Surviving examples of carving from this period are recognisable as having been made with stone tools.

Numbers of human kind were never large. Small whanau groups of perhaps thirty or forty kinsmen settled around the coast and on flatlands behind beaches, making a total of about twelve hundred. Some settlements were occupied for short periods when, for instance, fish were running in schools or forests foods were in season. As agriculture was developed the settlements became more permanent and located close to garden plots.

At the very beginning of human habitation, the island must have been still in its primeval state, with noisy birds inhabiting every level of the dense bush from the canopy to the bush litter. Many were ground birds with limited powers of flight. There were no land mammals except for two kinds of tiny bats; no rats, no mice, no cats, no dogs; no predators of any kind. Apart from birds and marine mammals, the only vertebrate animals were three orders of lizards, geckoes, skinks and tuatara.

The arrival of Polynesian settlers soon brought profound changes to the forest environment. Large flightless birds made easy pickings for the first human inhabitants and were soon hunted to extinction.

These are known only by bones found in middens and bone deposits in caves and swamps. Kiore, the Polynesian rat, stowed away on the great voyaging canoes. On making landfall kiore scurried ashore to forage and multiply rapidly and compete with the many bird species foraging in the bush litter and raising their young on the forest floor.

Maori agriculture required bush to be felled for garden plots, but it was not until the 19th century that European farmers and timber merchants cleared the forest. The sharp hooves of grazing sheep and cattle on lightly grassed hills started the process of erosion which gradually silted up the estuaries which once ran deep and clear into the hinterland.

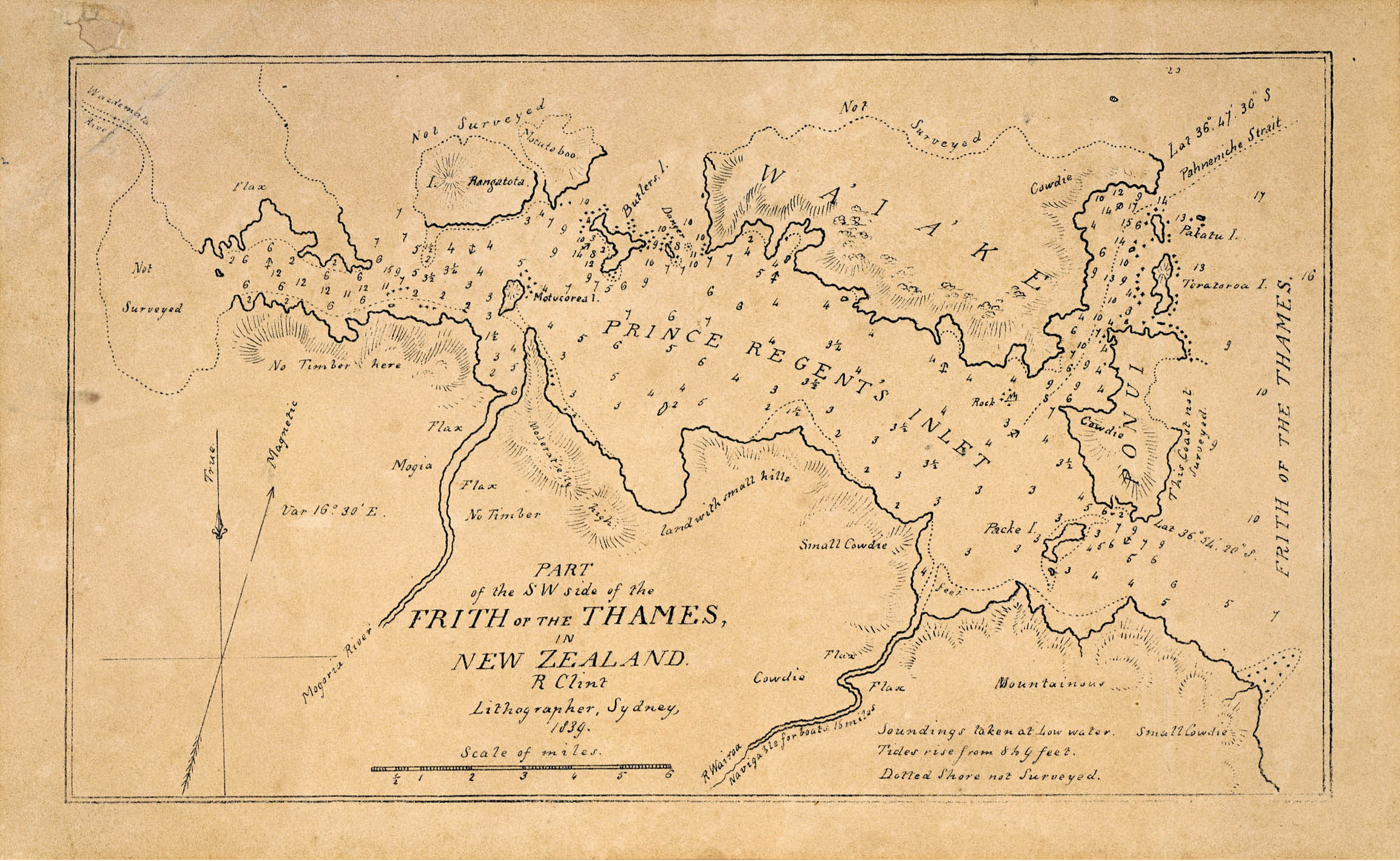

The “long sheltering island” was already known by Maori as Waiheke when European visitors first asked for a name. The full name, Motu-Wai-Heke means island of trickling waters, or descending waters. (The Maori word for cascade is hukere). The deep forest litter absorbed the heaviest rains to be slowly released in trickling streams of pure clear filtered water. The island was widely known among Maori for its abundant water. In 1820, James Downie, the master of the store ship HMS Coromandel made a chart of the Tamaki Strait and the Coromandel coast. He labeled the island Motu Wy Hake, spelling the name as he heard it.

A detailed account of the long and sometimes turbulent history of Maori occupation of Waiheke can be found in two books by the historian and Waiheke resident Paul Monin: Waiheke Island: a History and Hauraki Contested, 1769 – 1875.

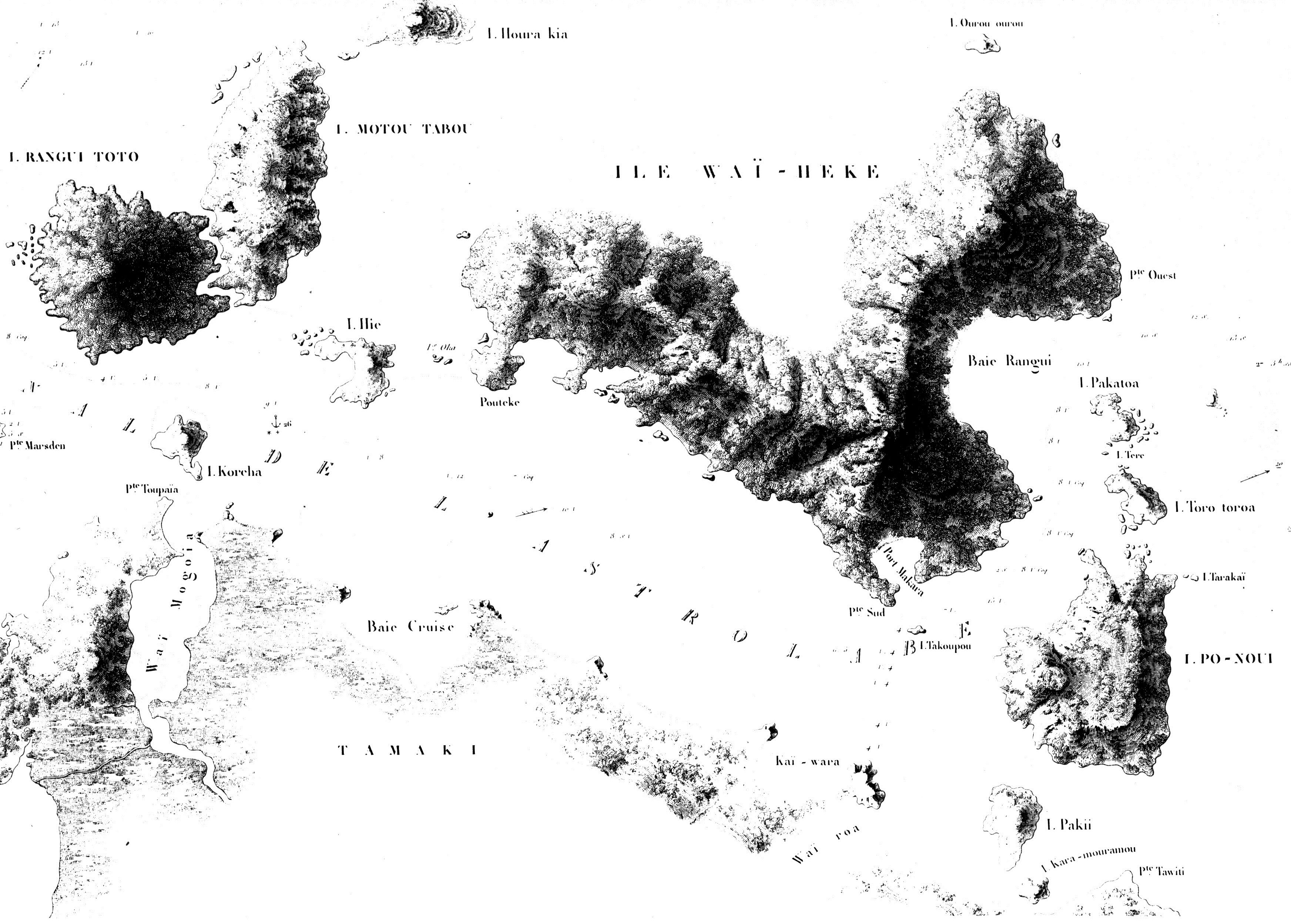

This was drawn by the French explorer Capt. Dumont D’Urville during the expedition of the Corvette “Astrolabe”. It is remarkably inaccurate. Note that Capt. D’Urville named today’s Tamaki Strait after his ship “Canal de l’Astrolabe”.