Waiheke Island Historical Society

P O Box 206, Ostend, Waiheke Island 1843, New Zealand

|

Waiheke Island Historical SocietyP O Box 206, Ostend, Waiheke Island 1843, New Zealand |

[This article is adapted from a talk given by Jan Scott to the Waiheke Island Historical Society on 27 March 2011. It was published in the Waiheke Weekender on 18 June 2011.]

Solanum tuberosum.

Those who doubt the importance of biodiversity in food crops should study the great potato famine that struck northern Europe, especially Belgium and Ireland, during the late 1840s. This famine not only starved over a million Europeans, but it very nearly altered the course of Waiheke history.

The potato is native to the western coast of South America, where there are over two hundred species of them. Potatoes thrive in cold, harsh climates, and for this reason the Spaniards, in about 1560, brought a shipload of them to Belgium, which they then controlled. As it happens they brought only one species, Solanum tuberosum. Nonetheless this single shipment of potatoes spread to become the main food staple of northern Europe, displacing grains such as wheat and rye. A major reason for the potato’s success was that Europe, which had never seen a potato before 1560, was free of potato diseases such as the oomycete fungus.

But it was only a matter of time before the fungus found its way to Europe, and when it did, the results were disastrous. This happened in the spring of 1845, when a shipment of potatoes infected with “potato blight” (the oomycete fungus known as Phytophthora infestans) arrived in Belgium. Potato blight had been a problem in Mexico and the United States for several years, but it did not cause a famine there because it affected only some of the hundreds of species of potato found in the Americas. Unfortunately Solanum tuberosum was one of them, and within weeks of reaching Belgium, the blight destroyed 87% of that country’s potato crop. By the following spring the blight had spread to the rest of northern Europe, where the effects were especially catastrophic for Ireland. Potato fields were wiped out, and for millions of people there was literally nothing else to eat. Between the deaths that the blight caused and the emigration that it provoked, the population of Ireland plummeted and has never recovered to its 1845 level.

Framed portrait of Adèle Célestine De Witte, née Gillodtz,

wife of Charles De Witte. She died in 1864.

All of these tragic events were watched from Waiheke with great concern by a Belgian named Charles De Witte, who with his wife Adèle and their young daughters had immigrated to New Zealand in 1842. Charles De Witte was the Belgian consul to New Zealand and lived in St Georges Bay in Auckland, but he spent much of his time on 207 acres of land that he acquired on Putiki Bay. He and his son-in-law Laughlin O’Brien (whose marriage to Hélène De Witte was celebrated by Bishop Pompallier himself) expanded the Putiki holdings by purchase from neighbouring Maoris until they owned over 2500 acres in a thick arc stretching from Te Whau Point almost to Woodside Bay.

Charles De Witte’s idea to relieve the suffering of his countrymen involved a stupendous project: the resettlement of 200,000 Belgians to Waiheke Island. In 1985 Jan Scott, whose home in Rocky Bay would have been in the middle of the proposed settlement, conducted some preliminary research on this project. According to Jan, the Belgian Consulate in Wellington holds archives of De Witte’s correspondence with his brother Léopold and others in Belgium during the 1840s and 1850s. Through Léopold’s influence with the Belgian government and Adèle’s rumoured connections with the Belgian royal family, Charles amassed the political and financial support needed for his project. The plans for a Belgian city on Waiheke were drawn up, the ships were organised; and then nothing happened.

“I couldn’t find out why it didn’t happen,” says Jan. “I didn’t have time at that stage. I’m hoping someone will take over the research and run with it. There’s a challenge for you! Can you imagine what Waiheke would have been like if we had had 200,000 Belgians settle here? Certainly we would have had a better standard of coffee!”

Such an influx of French- and Flemish-speaking settlers would have changed the course of history not only for Waiheke, but for New Zealand as a whole. In 1850 the British population of the colony was only about 22,000, and the Maori population maybe three times that. If De Witte’s dream had been realised, over two-thirds of New Zealand’s people would have been Belgian; in fact Waiheke would have been more populous than any city in Belgium at that time.

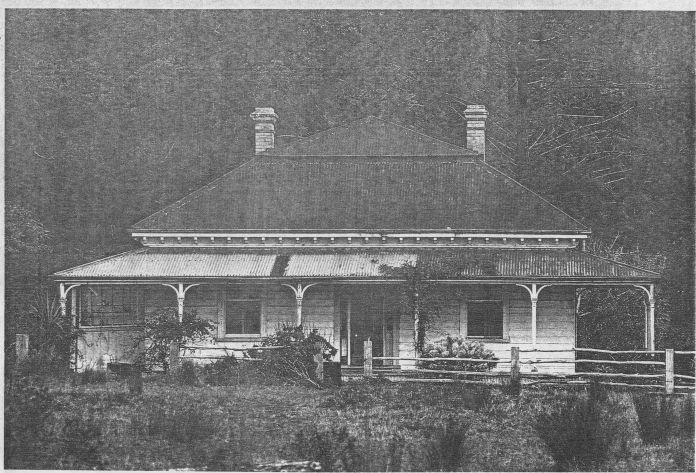

The O’Brien family home, called “Wharetana”, was located

on Wharetana Bay on the northern side of Te Whau

Peninsula. It was built in the 1840s and enlarged in 1860.

For whatever reasons, the De Witte plan fell apart; and in the 1920s Laughlin O’Brien’s sons Dolph and Jack began to subdivide and sell off their land to form the town of Omiha or Rocky Bay. The O’Briens still maintained a large farm, and their cattle, unconcerned by the change of ownership, continued to graze amongst the houses and baches of Rocky Bay. “One night,” says Jan, “our house started to shake. We thought it was an earthquake, but it was only a cow that had got stuck between the bach and the bank.”

The last of the O’Brien farm was sold in 1963 to Robert and Maureen Rothschild, who wound up owning what is now the Whakanewha Regional Park and adjoining lands as far as O’Brien Road and beyond. The Rothschilds, from New York, were not interested in farming. In fact Maureen Rothschild had a development scheme in mind that bore a certain resemblance to the De Witte plan of a century earlier, although not quite to the same scale. She wanted to start a hydrofoil service between downtown Auckland and Whakanewha Bay, like the one that was then serving Matiatia, and build a community of 5000 condominium townhouses similar to ones then emerging along the Hudson River and on Long Island, New York. The socioeconomic class of her proposed community can be gauged by the fact that it would have been centred around a helipad located where the dotterel breeding ground is today.

“You can imagine the articles and letters in the local paper back then, and the furore that the whole idea created. And there again I’m not quite sure why it didn’t fly,” says Jan Scott. “But we’re very lucky that we’ve got the Whakanewha Reserve there now.”