Nobody paid much attention to Prince Abdulazziz, the Saudi oil minister, in May 2008, when he blamed high oil prices on financial speculators. It seemed he was just trying to deflect attention from the extra billions his country was making from the skyrocketing price of its major export. After all, there were plenty of traditional supply-and-demand explanations for the price spike: surging demand from new oil-thirsty economies, especially in China and India; supply disruptions caused by hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico and political instability in many producing countries; and above all the passing of Peak Oil, which guarantees that from now on, each drop of oil will be more expensive to extract than the last.

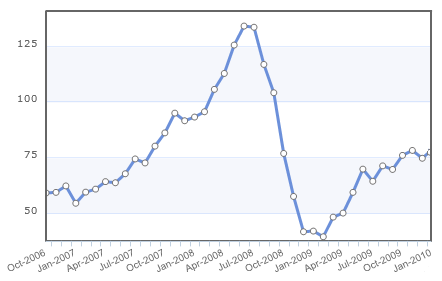

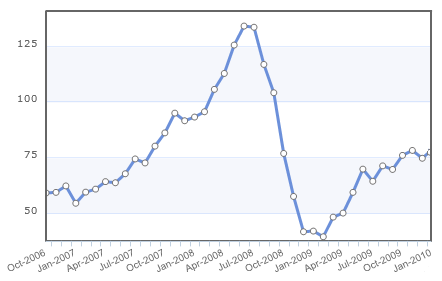

Yet two months after he spoke, Abdulazziz was proved right when the price of a barrel of oil began a plunge from $147 to $34 in the space of five months. It then recovered and finally stabilised around $70. The rapid rise and even more spectacular fall bear all the teethmarks of a speculative feeding frenzy. It turns out that the classical forces of supply and demand accounted for only about half of oil’s price in mid-2008; the other half was pure speculative bubble.

Teethmarks of a speculative feeding frenzy:

crude oil (petroleum), West Texas Intermediate 40 API, Midland, Texas,

US dollars per barrel, October 2006 through January 2010.

Source: Index Mundi (www.indexmundi.com)

Today we see the same thing happening to food prices. We all know the structural causes of food price inflation: seven billion mouths to feed, rising prosperity (and meat consumption) in Asia, declining supplies of fresh water for irrigation, agricultural disruptions caused by global warming, and the diversion of food crops to produce biofuels. But again, these don’t tell the whole story.

International trade in both oil and food takes place in commodity exchanges, the largest of which is the 160-year-old Chicago Board of Trade. These immense exchanges provide a forum where the forces of supply and demand play out between sellers (from Australian beef stations to Saudi oil producers) and buyers (Foodtown, McDonalds, petrol station chains). Speculators have always been present too, buying commodities for future delivery when they think prices are low, with the intention of selling the contract long before any actual delivery would have been made. Historically the speculators have made up about 20% of the market; the others, the “real” buyers and sellers, have tolerated the speculators because their constant activity provides a sort of liquidity to the exchanges. That is, even in the worst of times a seller can find a speculator who will pay something for the goods in question.

All this changed with the deregulation of the financial markets in the late 1990s. Until then, you had to have something to do with producing or consuming commodities in order to participate in the great exchanges. After deregulation, however, big banks, insurance companies, investment houses, and anyone with lots of cash could play. The results should have been predictable. The main vehicle for the speculators, called commodity index funds, grew in value from $13 billion in 2003 to $240 billion in 2008.

The dynamics of the commodity exchanges suddenly reversed: Instead of the “real” traders owning 80% of the market, now the speculators had four or five times the firepower of those who actually produced or used the goods in question. Their short-term tactical decisions, and not the traditional laws of supply and demand, would henceforth drive the prices of oil, food, and everything else. And the direction that it would drive them was up.

At first, no one seemed worried about the consequences of such a shift. In 1999, most of the speculators were absorbed in the dot-com boom, which burst so spectacularly the following year. Then sub-prime mortgages became the speculative fashion, until that bubble burst too in 2007. But once the global recession took the lustre off of the share and debt markets, speculators turned their attention to the one market with a guaranteed minimum demand: commodities. What, after all, could be a safer investment than food?

The answer, unfortunately, is that once the speculators take over, commodities are no safer an investment than anything else. Look at oil, for example. The well-founded belief that oil will be more and more expensive to produce should make it an ideal long-term investment: Buy an oil contract at today’s prices, and sell it at tomorrow’s prices, and you should make a profit. So some speculators buy oil contracts, and their massed demand drives the price up. Other speculators notice this, and rush to join in, pushing the price higher. Wall Street firms point to the rising price as proof of their investment savvy, luring the common public into the game. Soon it’s a frenzy, with the actual producers and consumers of oil swamped by the speculative tides.

A speculative bubble is just like pyramid or Ponzi scams, in that the illusion of prosperity depends entirely on increasing numbers of suckers entering the market, to bid the price up. Since the supply of suckers is finite, eventually the bubble will burst, the price will plummet, and the majority of those who thought oil was a safe investment will be facing big losses. But a minority — the cynical manipulators who knew it was a bubble all along, and sold while the going was good — will make immense profits. So will the banks and investment houses that manage the trading, because they take a commission on each transaction — and during a bubble, there are lots of transactions.

This is what is happening to food prices right now. Investment bankers like Goldman Sachs, Barclays and Deutsche Bank sell index funds to the public based on everything from palm oil to wheat to livestock. People buy shares in these funds in the belief that food prices will go up, and indeed they do; but the rise is due to more investors pouring into the market, rather than to the real pressures of supply and demand. In other words, it’s a bubble.

If the oil price bubble is anything to go by, food prices should collapse in a year or two, but don’t count on the consumer enjoying any of the relief. It will all be absorbed by the middlemen. (Did you notice Fullers’ fares returning to 2003 levels when the oil price collapsed? I didn’t.) Meanwhile, farmers will see a sudden drop in income, but no drop in the costs of seed, fuel, fertiliser, and other commodities that had been keeping pace with the price of food.

It’s a system of orchestrated chaos, from which only the orchestrators can benefit. This is about as far removed from a classical free market as you can get, because innovation to correct imbalances is not possible; it is the banks and investment houses who hold the purse-strings for all new investments, and they are not going to support anything that challenges their own supremacy. This is why we are hearing even some conservatives, with their fundamentalist faith in the free market, beginning to express some timid sympathies with the Occupy Wall Street movement.

The growing distortion of the traditional market forces by this new and immense speculative power has had social and political repercussions that are missed, or deliberately ignored, by most of the facile commentary that we get in the media. It’s no accident that the unrest in the Arab world, the Eurozone debt crisis, and the various Occupy movements have all coincided with the commodities bubbles. These movements all have their roots in the same financial dysfunction.

First and foremost, of course, is hunger. Food prices are high enough just from population pressures and the limitations of ecology. When they double again due to financial games played in distant commodity exchanges, ordinary people get understandably upset. Their anger is not always directed at appropriate targets, but it always reflects a sense of powerlessness at an all-to-obvious redistribution of wealth from the many to the few.

Second is the corruption of financial institutions. The social purpose of banks and investment houses is the concentration of financial resources to fund projects, both private and public, that meet people’s needs. This is a laudable long-term goal, but the immediate incentive for banks’ decision-making is short-term profit. There has always been a conflict between purpose and incentive, but now that speculation represents such a large percentage of a bank’s activity, the bank’s behaviour loses nearly all of its social purpose. There is very little actual investment in industries, projects, and social programs that create jobs or make people’s lives better. Banks and investment houses, or at least the large ones, have become mere parasites, capitalising on their monopoly over the flow of money.

Third, with the corruption of financial institutions comes the corruption of political institutions. The main threat to banks’ continued control over the economy comes from the possibility of government regulation, so naturally the banks use their financial power to influence elections. You can see the results all over the world.

In America, one expects the Republican Party to cater to big business interests, but it has been Democrats who have done the most damage: Clinton deregulated the commodities market in 1999, and Obama has championed a Wall Street bailout costing hundreds of billions of dollars. This shows the power of money to influence even the most ostensibly liberal of politicians. Even the Supreme Court has been affected. How else could one explain the court’s January 2010 decision that a corporation has the same rights as a flesh-and-blood citizen to free speech — and, explicitly, that donating money for political advertisements is a form of free speech?

In Europe, the banks’ collective failure to finance social investments, and the politicians’ well-funded refusal to compel them to do so, has led directly to the debt crisis that threatens half the countries of the continent. The diversion of money from investment to speculation has resulted in a stagnant economy, and governments have been forced to borrow money — from the banks, of course — to fund public welfare programs. Now that several European governments are unable to repay the loans, the banks are in a position to demand crippling austerity programs and yet another bailout.

In New Zealand, our main protection against this kind of speculative corruption has not been the Labour party as one might have hoped (just look at David Lange’s record on financial deregulation for proof of this), but the advent of MMP.(1) When small parties can throw their weight around in proportion to their support, and the two major parties have to form coalitions with them, the political process has too much ferment to control easily. This is why the big money prefers a first-past-the-post system, such as they have in America and the UK. If anyone wonders where the money is coming from to fund the campaign against MMP, just remember how much easier it is to buy off two parties than six.

So the net result of the growth of commodities speculation has been to undermine the two great rationalist foundations of Western civilisation: democracy and the free market. For two centuries, these two foundations have provided us with a robust meritocracy that, imperfect though it might be, has withstood attacks from monarchist and clerical interests, from fascism and Stalinist communism. It has conquered slavery; it has proved stronger than pig-headed instincts regarding race, gender and nation. When we next face a challenge from some alien mode of social organisation — from fundamentalist Islam, or a resurgent China, or a revanchist Russia, or some internal Napoleon — will our foundations prove so worm-eaten with corruption that we collapse?

Waiheke Island, November 2011

(1) MMP: Mixed-Member Proportional, a voting system in which a parliament is composed of both electoral-district members and party-list members such that each political party’s strength in parliament reflects its percentage of the national vote. New Zealand adopted MMP in 1996.

[ Return to Travelogues & Commentary index ]

Copyright © 2011 T. Mark James

This article first

appeared in the Gulf

News,

Waiheke Island, New Zealand, on 1 December 2011.